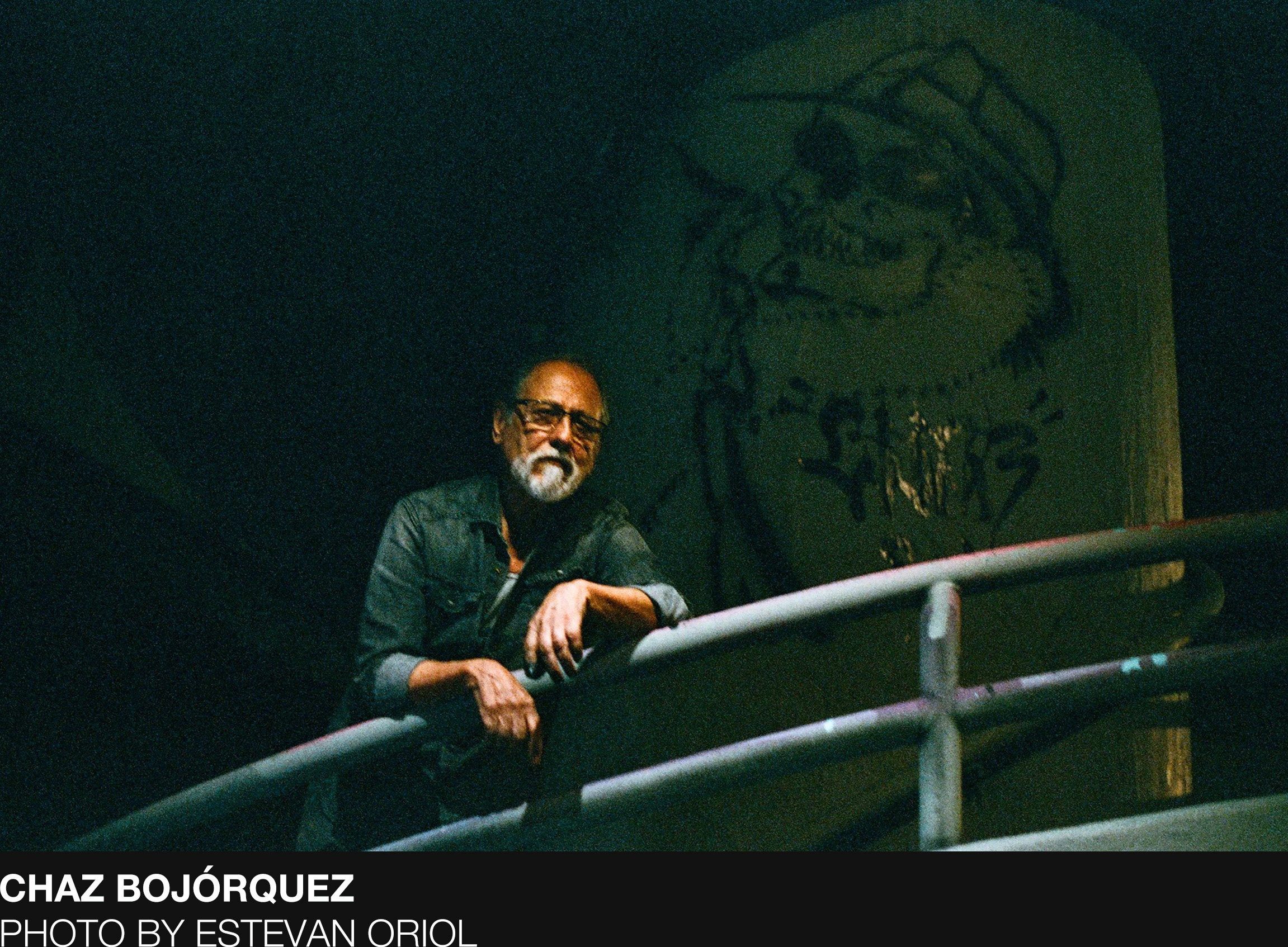

WHO IS CHAZ BOJÓRQUEZ?

The Origin of Los Angeles Visual Language

To understand Los Angeles visual culture, you have to understand writing.

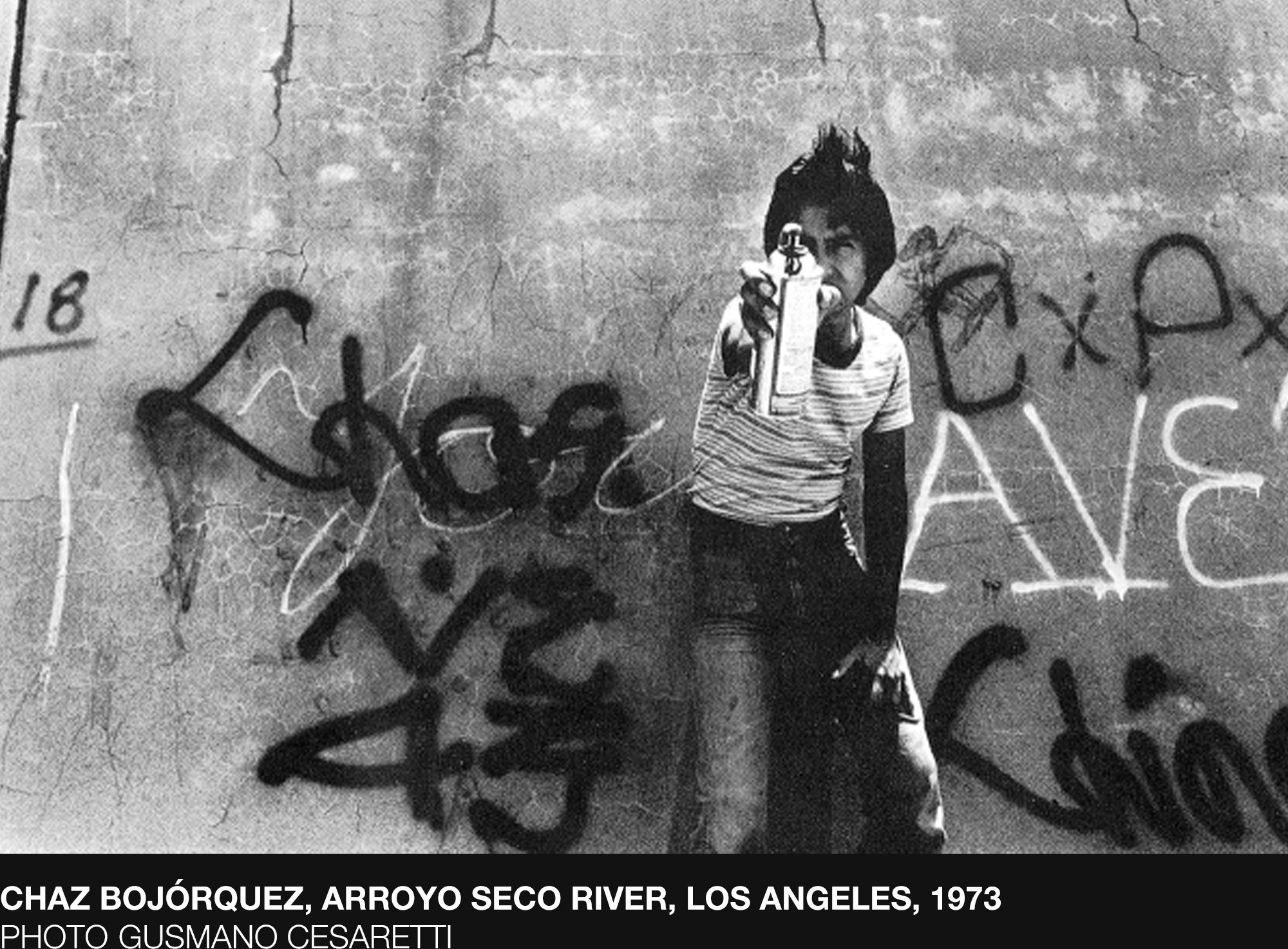

Long before graffiti became a global movement, and long before street art entered galleries and museums, Los Angeles already communicated through its walls. Names, symbols, and hand-painted lettering marked presence, identity, loyalty, and territory. This was not rebellion, nor spectacle. It was communication — a visual language embedded in place, community, and lived experience.

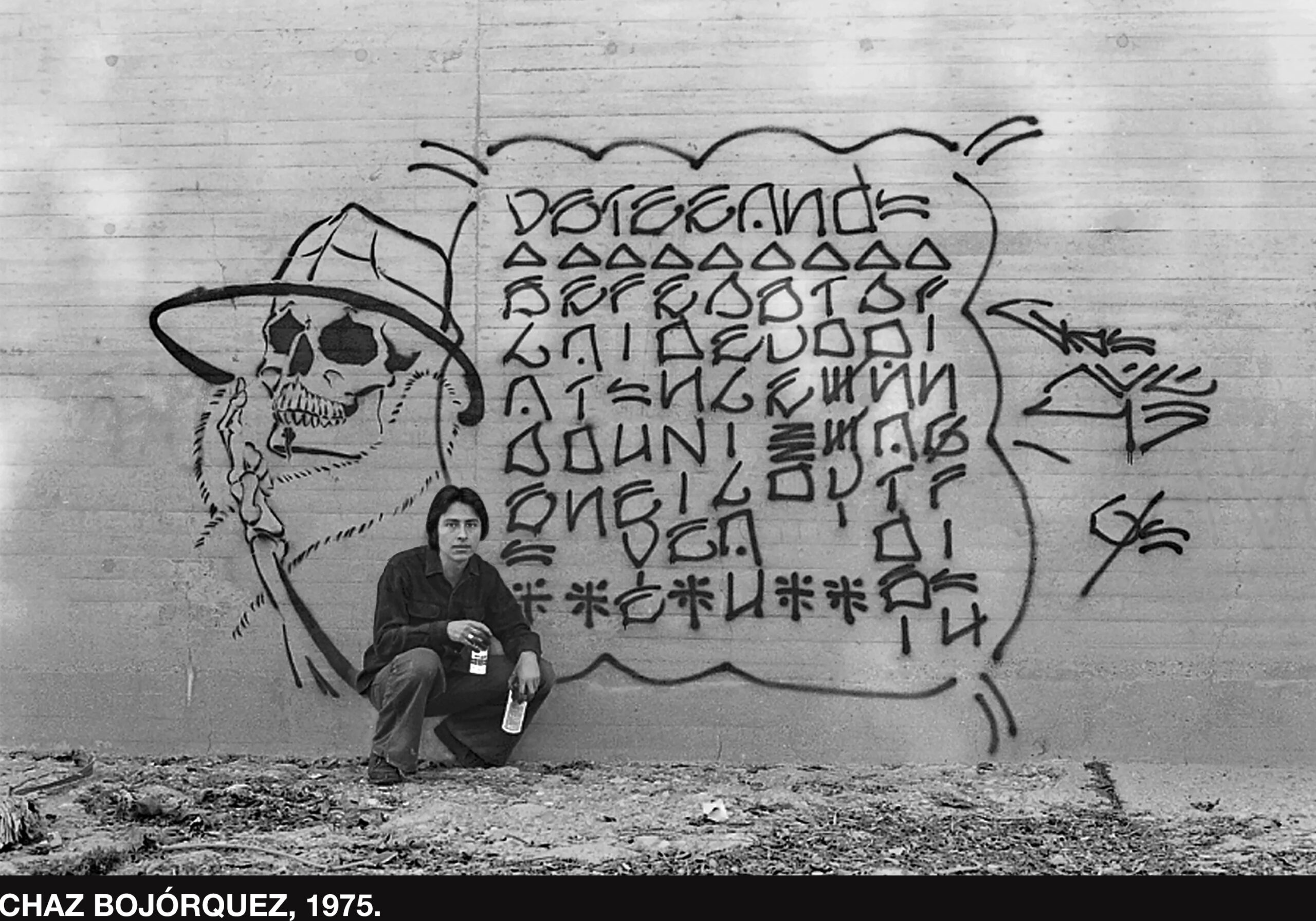

At the centre of this lineage stands Chaz Bojórquez, a foundational American artist whose work predates graffiti as a defined movement and helped establish writing on walls as cultural authorship rather than decoration. Widely recognised as the Godfather of Cholo Writing, Bojórquez is not a reinterpretation of graffiti culture. He is one of its origins.

Roots in East Los Angeles

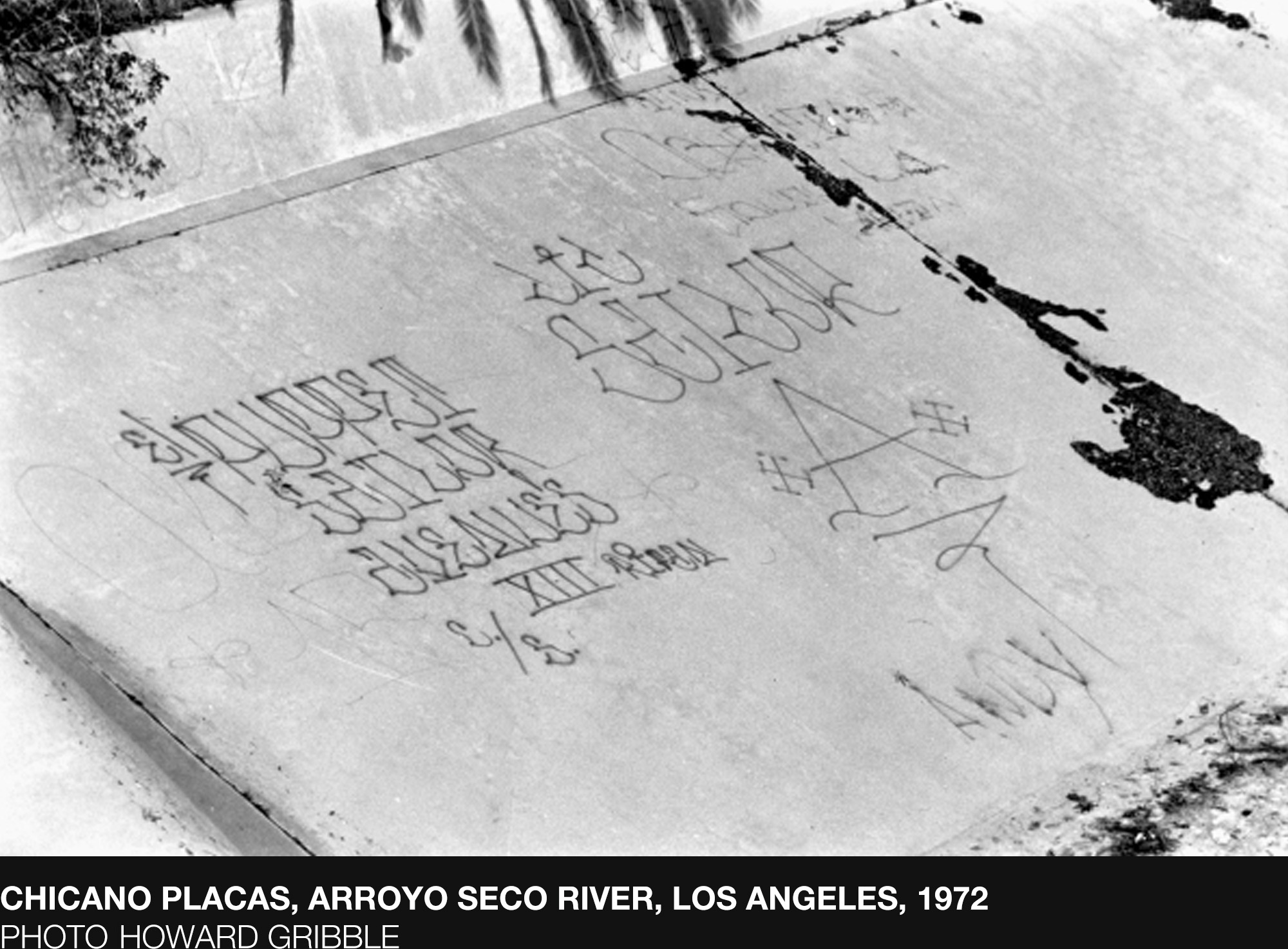

Born in 1949 and raised in Highland Park, East Los Angeles, Bojórquez grew up immersed in the visual language of placas — hand-painted roll calls used within Mexican-American communities to mark presence, identity, and respect. These markings were not aesthetic gestures or acts of rebellion; they functioned as social language, embedded within neighbourhoods and daily life.

Cholo writing existed long before graffiti gained international visibility and developed independently of the spray-can culture that would later dominate popular narratives. Bojórquez’s practice emerges directly from this context. From the outset, writing was not about fame, speed, or competition. It was about authorship — about making oneself visible within a specific cultural environment.

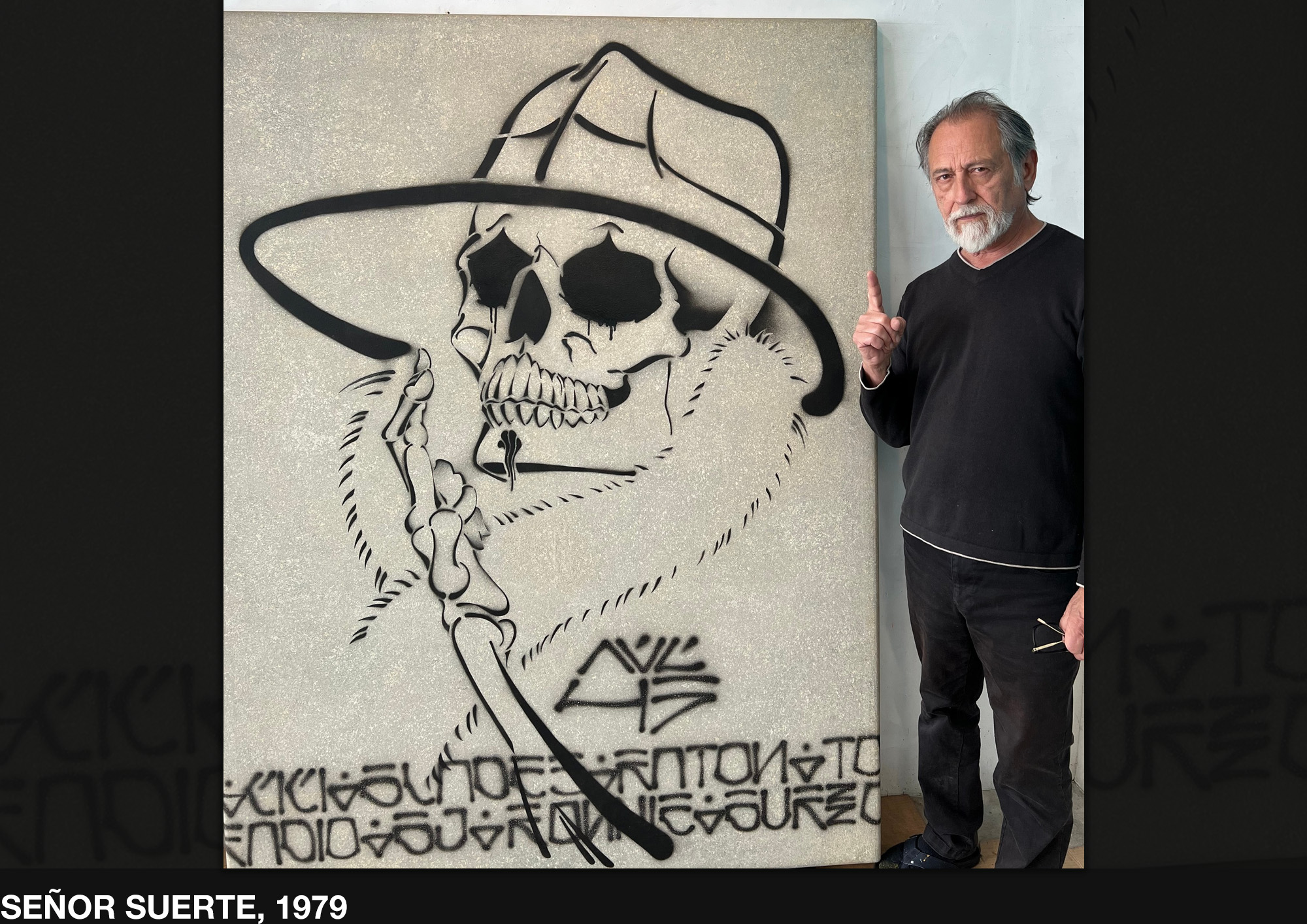

Señor Suerte: A Foundational Image

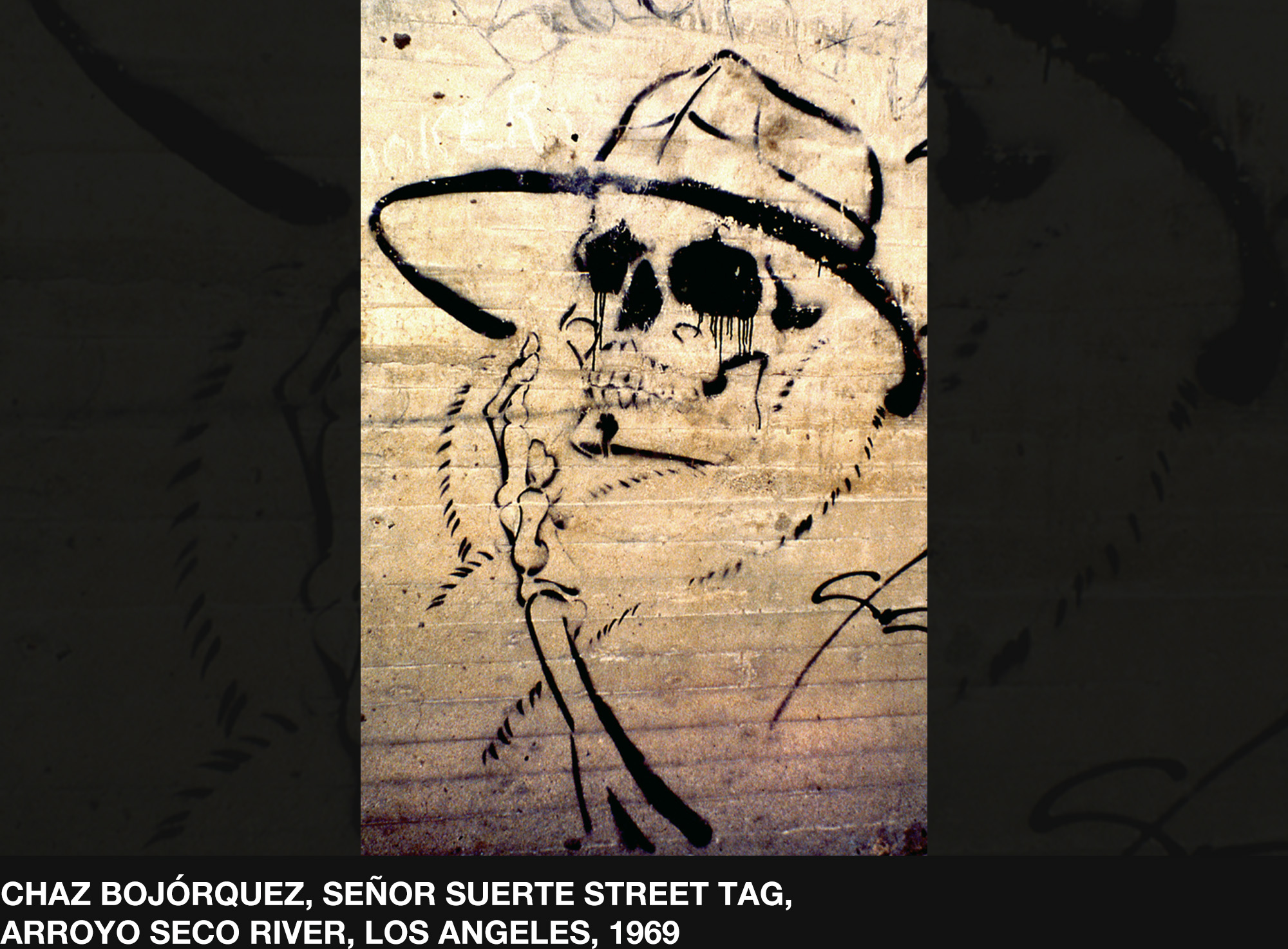

In 1969, Bojórquez created Señor Suerte (Mr. Lucky), a stylised skull rendered as a stencil and repeated across Los Angeles. Originally painted on a pillar along the Arroyo Seco Parkway, the image carried layered meanings of mortality, protection, and survival. As it reappeared throughout the city, it became one of the earliest recognisable recurring street images in Los Angeles, long before the term “street art” existed.

What distinguished Señor Suerte was not scale or provocation, but intent. It was not a tag, a name, or a territorial marker. It was a designed symbol, and its repetition established recognition through authorship rather than competition. Over time, the image embedded itself into street and prison culture, appearing as tattoos and visual shorthand across communities.

This moment proved something new: writing on walls could function as cultural authorship, not merely as marking.

Art Training, Discipline, and Control

Unlike many artists working on the street during this period, Bojórquez combined graffiti practice with rigorous formal training. He studied painting and ceramics at Chouinard Art Institute (now CalArts), painting at California State University, Los Angeles, calligraphy at the Pacific Asia Art Museum under Master Yun Chung Chiang, and Pre-Columbian art in Guadalajara, Mexico.

This grounding in drawing, typography, and global writing systems remains central to his practice. Bojórquez has consistently emphasised drawing as the foundation of his work, favouring brush and paint over spray for the level of control, balance, and intentionality they allow. His letterforms are precise and deliberate, informed by discipline rather than impulse.

As a result, his compositions feel resolved rather than reactive. Every line carries weight, and every mark is considered.

From Street to Studio: A Conscious Evolution

As graffiti culture expanded globally during the late 1970s and 1980s — with the emergence of crews, style hierarchies, and visibility economies — Bojórquez made a conscious decision not to follow that trajectory. Rather than chasing scale or notoriety, he chose to refine his practice.

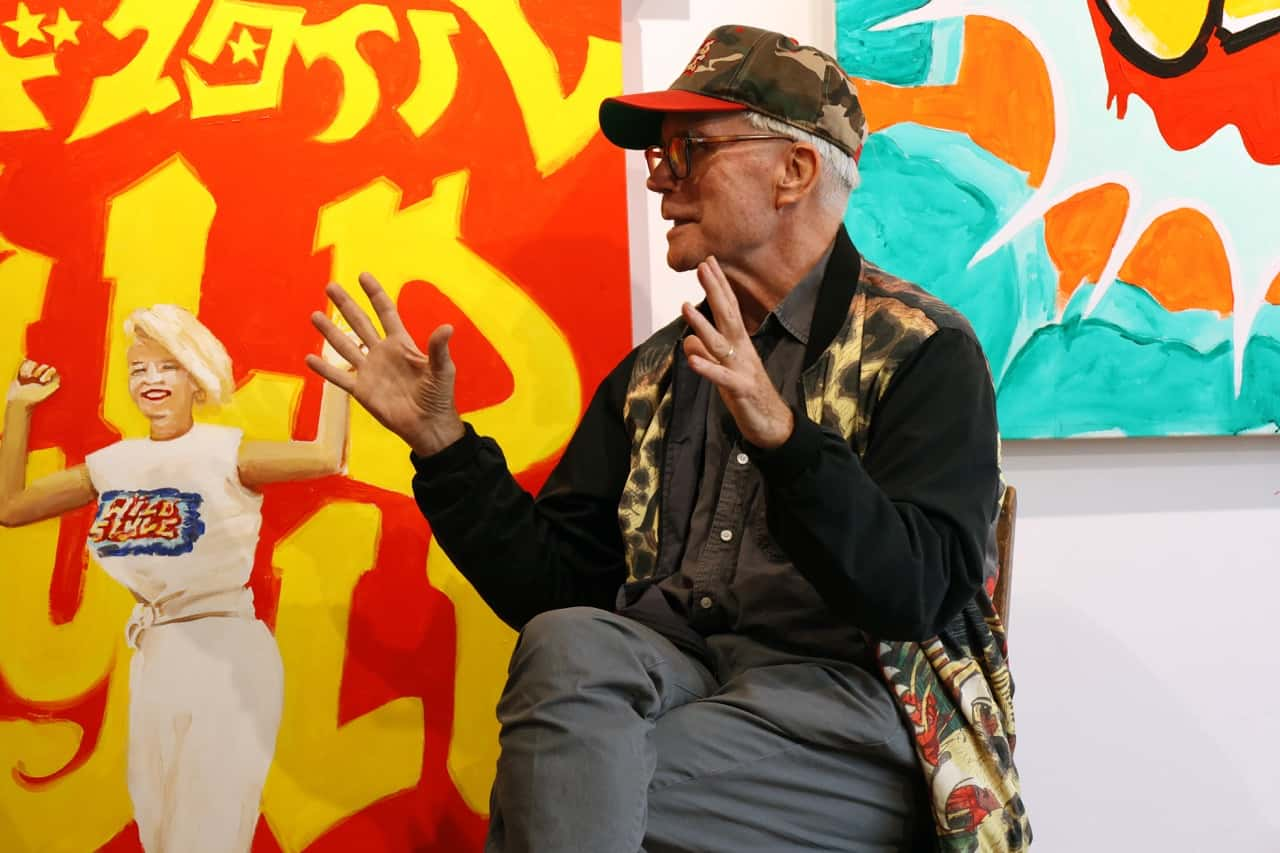

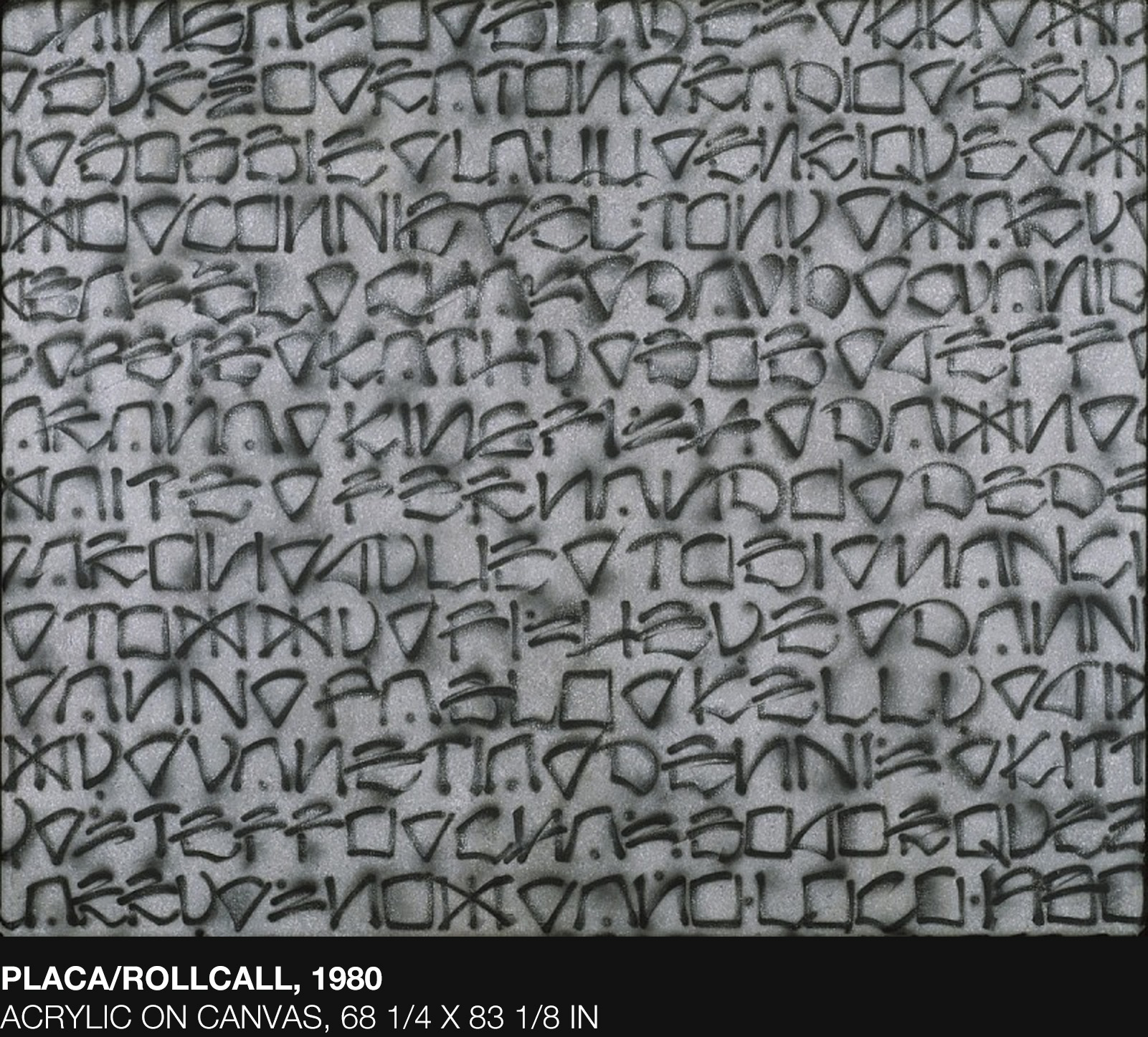

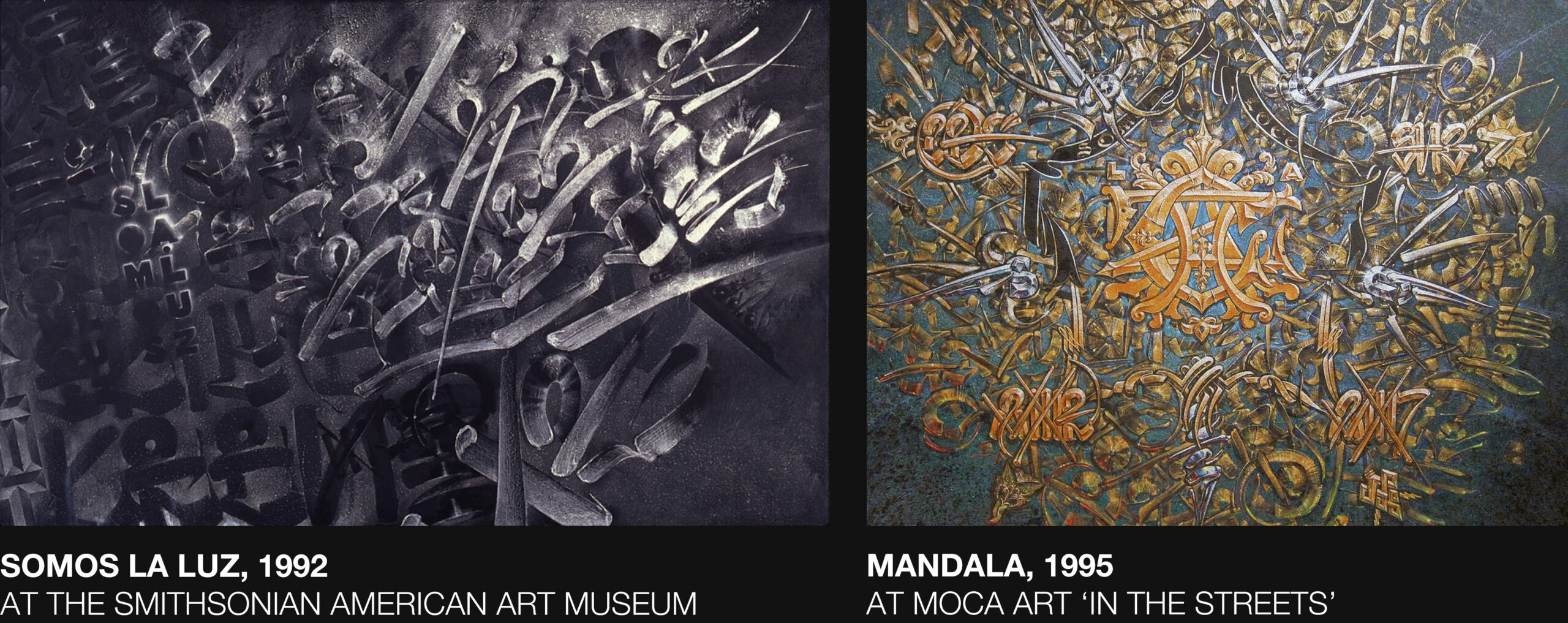

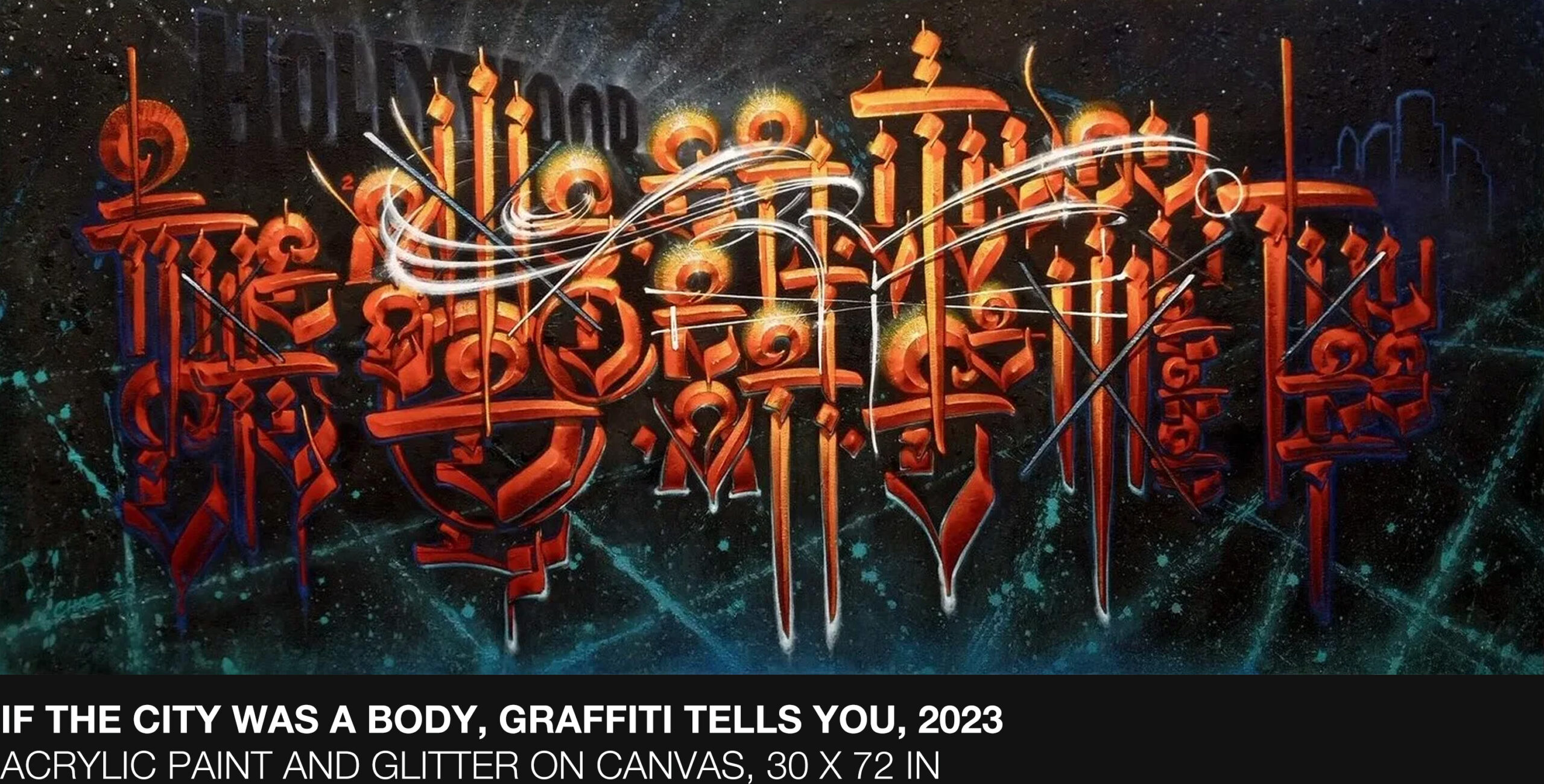

In 1979, he placed Señor Suerte onto canvas for the first time, marking a thoughtful transition from public space to fine art. Around the same period, he undertook a self-directed global research journey, studying writing systems, glyphs, tattoos, and calligraphic traditions across cultures. Upon returning to Los Angeles in 1980, his work evolved into a distinctive synthesis of Old English typography, Asian calligraphy, and cholo writing.

This evolution was not a departure from the street, but a deepening of its language. The resulting works are layered and architectural, echoing the accumulation of marks on urban walls while maintaining formal clarity and compositional restraint.

What Makes Chaz Bojórquez Different

Bojórquez did not adapt graffiti into art. He brought art and language into the street before graffiti had rules.

His practice is defined by writing as language rather than image, by repetition as authorship rather than branding, and by identity over visibility. This is why the designation “Godfather of Cholo Writing” functions not as a nickname, but as historical recognition. Bojórquez articulated and elevated a writing tradition rooted in community, structure, and cultural memory.

He represents origin, not reinterpretation.

Institutional Recognition and Legacy

Bojórquez’s significance has been established through history and institutional validation rather than trend or market momentum. His work is held in major permanent collections including the Smithsonian Institution, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA), and the de Young Museum.

He has exhibited extensively in museums, galleries, and institutions internationally over more than five decades, and is the author of several influential publications that have helped shape critical discourse around graffiti, lettering, and street-based art. In recognition of his lasting contribution to art and visual culture, he was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters by the Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles.

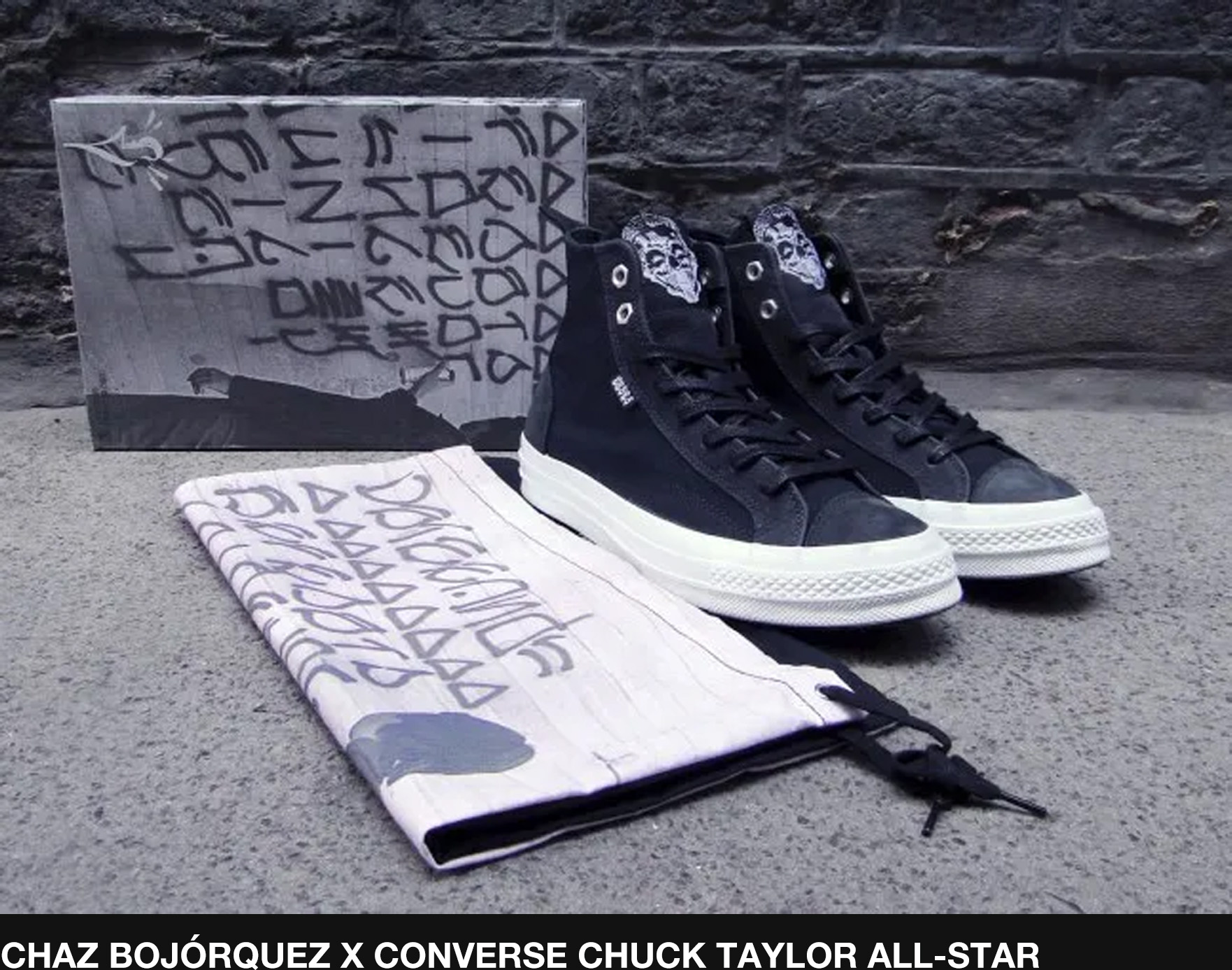

Influence Beyond the Gallery

Beyond fine art, Bojórquez’s influence extends into film, fashion, publishing, and design. His lettering has appeared across textiles, objects, and cultural projects worldwide, including collaborations with Nike, Converse, and Levi’s. These partnerships reflect not trend adoption, but the enduring relevance of his visual language.

His work continues to resonate precisely because it is rooted in language rather than style.

Collecting Chaz Bojórquez

To collect Chaz Bojórquez is to engage with a foundational chapter in Los Angeles visual culture. His work represents writing as authorship, a visual language refined over decades, and cultural history whose significance has already been established through scholarship and institutional recognition.

Rather than responding to market cycles or stylistic trends, Bojórquez’s practice offers collectors long-term cultural relevance. His works are understood not as isolated objects, but as part of a broader lineage — one rooted in place, identity, and the evolution of visual language itself.

Chaz Bojórquez at Woodbury House

Chaz Bojórquez continues to live and work in Los Angeles, maintaining an active studio practice closely connected to the cultural foundations from which his work emerged.

At Woodbury House, we are proud to represent Chaz Bojórquez, a foundational figure whose work offers collectors and institutions a direct engagement with the origins of an entire visual language — one grounded in culture, discipline, and history.

Chaz Bojórquez is not concerned with trend, hype, or nostalgia.

His work is rooted in origin, language, and authorship.

When this is understood, the work speaks for itself.